The Whippet #91: Evil self-replicating origami

On this page

Hello!

Today's Whippet is written in between naps, because I just had dental surgery. So I hope it's coherent. It's pretty cool, my upper jaw was too thin so they've cut into it and put granules of cow bone in it. Over the next few months, my own bone will grow around the cow bone bits, and I'll be a proper hybrid. Like a centaur. Exactly the same and as cool as a centaur.

For now though, I'm just giving strong chipmunk energy on the left half of my face.

(Photo by Diana Marshman)

Why the Spanish Flu pandemic was so unusual

Re: the coronavirus, people understandably want to know what's going to happen, and to make guesses, they look at previous pandemics. This is all very logical except that viruses are as different from each other as mammals: it's like looking at a bat to predict how a giraffe will behave.

So with that in mind, no one drawing any conclusions about coronavirus, let's talk about why the Spanish Flu was so weird!

Most diseases (such as the regular flu) are most dangerous to sick, the elderly, and people with compromised immune systems. For pretty obvious reasons.

The Spanish Flu was the opposite: the people who died were young and healthy, people in their 20s and 30s. This is because it happened during World War 1.

Normally, very sick people stay home and mildly sick people go to work, so viruses, through natural selection, evolve towards milder forms - these are the forms that are successfully breeding. This is why bad flu pandemics are so rare - it's not just good luck, it's that however severe they begin, they always tend to evolve to become more mild.

In WW1, however, everything was topsy-turvy. Mildly sick people stayed at the front and very sick people were packed onto troop trains and massive crowded field hospitals - that was where the virus spread. So the more severe versions got more opportunities to spread and became dominant. Also, the versions that hit soldiers - young healthy people - were the ones that were most successful.

The theory is that the Spanish Flu caused a 'cytokine storm' - your immune cells have an overwhelming inflammatory response that damages you. So the stronger your immune system, the more damage it does. [Wikipedia: Spanish Flu].

A thing that's distinct about the novel coronavirus is that people don't have symptoms in the first 10 days or so . So people with both mild and severe forms will be going to work and interacting with people. That means the virus is unlikely to as quickly mutate into a mild form - but also unlikely to mutate to become more severe, the way the Spanish Flu did. This last paragraph is speculative and I'm not an epidemiologist so feel free to ignore it.

Why are there no good viruses? Also, let me tell you about PRIONS aka evil origami

I was wondering why bacteria can be harmful or helpful or neutral, but all viruses seem to hurt you. Given they just need a place to live, why can't they just hang out in your lungs and be chill, like bacteria can?

For people who didn't know: a virus is a totally different type of thing to a bacteria. In terms of how alive something is, philosophically, bacteria are a proper little animal. Some of them live in your body, some of them live freely out in the world, etc.

A virus doesn't have all the parts to be alive. It has dna, and a mechanism to inject dna, and that's about it. It can't eat or breed or survive outside a host. It's whole purpose is to find a cell and corrupt it into making viruses instead of whatever it was meant to do. People use the software/hardware analogy. A bacteria is hardware, and can exist on its own. A virus is a piece of software that changes how the hardware behaves.

So it can't just be chill and not make you sick, because it wants to convert your lung cells into more virus-producing cells. And you need those cells for breathing. So there's no compromise there.

NOW WE GET TO PRIONS

If a bacteria is fully alive, and a virus is half-alive, a prion isn't alive at all. A prion is a misfolded protein. When it touches another protein, it makes that protein fold wrong as well. But it's not 'infecting' it. It's not a living thing, and it's not doing survival of the fittest stuff the way a virus is. It's not trying to replicate itself. It just misfolds proteins it comes into contact with the way that acid burns stuff it comes in contact with. It's just... physics.

Prions are, most famously, what causes mad cow disease. Or kuru, which is caused by cannibalism.

Each prion turns every protein it encounters into another prion, with no mind or will, until you're nothing but misfolded proteins. And since it's not alive, it can't be killed. Mad cow disease is completely incurable: once you're infected, that's it. The only way to stop a prion is to cook it (you will know from cooking meat that cooking completely changes the nature of a protein).

Prions are self-replicating origami that cannot be stopped.

(I found this all completely terrifying until I remembered that mad cow disease has not in fact turned everyone in the U into protein origami, it seems to be pretty under control, so I can probably relax about prions.)

Thank you to science communicator Tom Lang who explained viruses/bacteria/prions to me, and specifically answered my question about whether viruses are alive in the way bacteria are with:

"I reckon life is when something can get up to trouble in a fairly independent and unpredictable fashion. Physics: predictable. Biology: unpredictable."

Scientists attempt to catch one dastardly rat

This is from a real scientific paper:

A single Norway rat released on to a rat-free island was not caught for more than four months, despite intensive efforts to trap it. The rat first explored the 9.5-hectare island and then swam 400 metres across open water to another rat-free island, evading capture for 18 weeks until an aggressive combination of detection and trapping methods were deployed simultaneously.

(It was studying: how hard would it be to stop a rat if it got to a rat-free island? Answer: put your money on the rat)

"Our findings confirm that eliminating a single invading rat is disproportionately difficult," the paper says.

This rat could be your guardian spirit, .

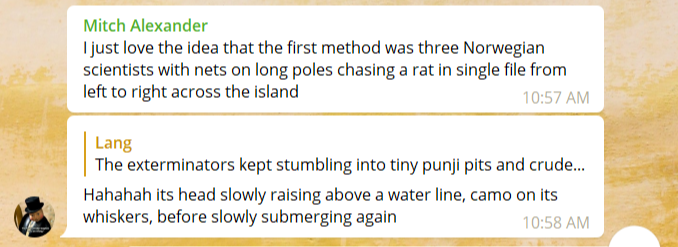

From the group chat:

#TeamRat

Dracula Parrot

actually called the Vulterine Parrot or Pesquet's Parrot.

Astonishingly beautiful essay by Wallace Shawn

(the actor who played Vizzini in The Princess Bride, and who I suppose I have quite wrongly not that thought of as a serious or poetic person)

It's about how actors see the world, and humanity, and it is full of so much empathy and warmth and love for humanity.

As with many of the best pieces of writing, it's hard to take just a snippet that would capture for you why it's beautiful. But it is.

Read it here.

(Don't worry about the title, it's not a screed.)

Unsolicited Advice

Accepting invitations that are weeks or months in advance

You know the thing when someone you like but don't love invites you to a party, and you say yes because you like them! Or someone invites you to some experimental thing that you wouldn't normally go to, but it would be cool to expand your horizons a bit.

And then when the day actually rolls around, when it's not hypothetical and you have to fit it in with your other plans or with your tiredness or your desire to spend time with your loved ones, you are like "oh my god why did I say Yes to that".

The problem is that when something is months in advance, you're comparing "Experimental Event" to "Nothing" and nothing of course seems more fun. But by the time you get there, there's a tonne of other things on, and you're now comparing the Experimental Event that you already committed to, to "dinner with beloved friend" or something you really love.

So here are two methods:

When someone invites you to something in the distant future, ask: Would I say Yes to it if it was this weekend?

That's the simple heuristic.

The more complicated one: Instead of comparing the event to doing nothing, compare it to the kind of nice event that you might do pretty typically. Like coffee with a good friend - you can't predict if some crazy opportunity will come up, but you can pretty reliably assume that if you go to this Event, that is one 'normal plan with nice friend' you won't be able to do. So that's what you should be weighing any future plans up against.

There are two main ways you can support The Whippet!

1. With money. A classic stand-by! Patreon lets you pay anything from $1 a month (50 cents an issue!) to infinity dollars a month (still infinity dollars an issue). It's not locked in or anything though, you can cancel/pause any time. Click here for Patreon

2. By telling a friend how it's good and they should read it:

Also, if you're not subscribed and you want to be, subscribe here!

Comments

Sign in or become a Whippet subscriber (free or paid) to add your thoughts.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.

A newsletter for the terminally curious

Arrives in your inbox every second Thursday.